Note: This Economic Update is a bit different than most both in subject and writing style. However, we still thought we had some personal insights and perspectives that were worth sharing. We’d enjoy hearing your feedback – good, bad or indifferent.

I have been intensely more interested in the situation developing in Ukraine over the past few months than those that circled Greece, a country of similar size, or Libya and the Arab Spring a few years ago. For the most part, I’ve taken geopolitical flare-ups in stride in terms of their potential impact to the stock market and the economy. In general, this approach has been the right one. (View a printable version of this Economic Update: Cold War: Thoughts on Ukraine Based on a Month Spent in Latvia)

Anticipating geopolitical events is nearly impossible, but it is equally as true that once concerns start to surface in the mainstream media, financial markets usually become far more skittish. At the same time, ever since the Gulf War, the markets have invariably enjoyed counterintuitive rallies once events progress from fear to reality.

On Monday, fears of Russian troops occupying Ukraine spooked global markets but, almost in a clockwork fashion, they rallied the next day when Vladimir Putin staged a press conference to explain his yet questionable intentions. While I think the overall strategy regarding the current geopolitical flair-up – standing pat – remains sound investment advice for the long term investor, I will also admit that it has worried me a bit more than most. The key difference may likely be familiarity.

I grew up during the Cold War and remember having real, childhood nightmares over the possibility of a nuclear war with Russia. At one point in high school, I had had a Russian friend whose parents had managed to escape the country with cartons of cigarettes lined with $100 dollar bills. They were extremely scared that anyone knocking on the door of their American home could be a KGB agent coming to deport them or even worse, eliminate them. A few years ago, when trying to locate “Eugene” for our 20th reunion, I called his parents, who repeatedly and suspiciously questioned me on who I was and why I was calling, even though the Cold War had long since ended.

I remember watching the Olympics during the seventies and my dad commenting about how “hot” the East German swimmers were, their muscles bulging in comparison to those in the outer lanes and who, in spite of the extra drag, chose not to shave their armpits. As a former college swimmer, I thought my dad might actually be serious about his declarations of love for the East German swim team, but also wondered why he would then marry my mother, who was so very feminine and frankly, very well groomed. Those who lived behind the Iron Curtain were only seen and heard from once every four years by the West, and when we did see them, it felt like we were observing humans from the “other” zoo.

The Sochi Olympics were a highly different affair than those I had watched growing up. We were far less concerned about nukes and roided up female swimmers and far more concerned about Bob Costas’ eye malady, how much Putin had spent on the games, and if Pussy Riot – the formerly jailed Russian punk band – would be allowed to lead a rainbow colored gay parade in Olympic Village. Instead of an ushanka-wearing Leonid Brezhnev, there was Vladimir Putin garbed in the Russian equivalent of Under Armour sportswear, dripping with the logos of what I would guess were Russian sponsors. Rumor has it that Putin socialized on multiple occasions with the Canadian Olympic team which, in hindsight, proved to be ineffective scouting efforts for the Russian hockey team.

In addition to living through the Cold War, perhaps I’ve not been doing myself any favors, having just read The Proud Tower and Guns of August, two highly regarded World War I related books by Barbara Tuchman. Some say that those who don’t learn from history are doomed to repeat it, but it could also be said that those who learn history might see parallels to events today that quite simply don’t exist. In this sense, ignorance can also be bliss.

My heightened sensitivity could also relate to the fact that I spent four weeks in Latvia a few months ago with my wife and youngest son. Latvia, for those that don’t know, is another former Soviet bloc country which, similar to Ukraine, regained its independence when the Soviet Union fell in the early 1990’s. While I might have hoped to cross a trip to Hawaii off my bucket list before taking a trip to Latvia, sometimes things just work out that way. The alternative option for us at the time had been Kiev, Ukraine, so at least on that front, the choice was a solid one.

While spending a month in Latvia certainly doesn’t make me an expert in Eastern European and Russian foreign affairs, I did pick up a few, first hand perspectives that haven’t necessarily been aired in recent media coverage of Ukraine. In a situation that could be similar to the consequences America faces today in supporting slavery early in its history, Russia may similarly be experiencing the consequences of seizing and occupying territory that at one time was not their own.

Following the end of World War II, Russia forced the migration of native peoples from Latvia and other annexed territories like Estonia and Ukraine to Siberia, replacing them with Russian nationals. This migration policy was a calculated one, meant to ensure cultural interbreeding and a generational shift of allegiance to Mother Russia over time. When the Soviet Union fell fifty years later, for the most part these large ethnic Russian minority groups stayed in the newly independent countries, having established lives and families of their own.

These ethnic Russian minority groups likely face considerable prejudice for what prior generations had done physically, spiritually and emotionally to the native populations throughout the former Soviet territories, similar to the real prejudice Israel may feel today or may be made to feel today in occupying the West Bank with the explicit support of America. If Native American Indian populations had a more powerful minority voice, I suspect we’d be hearing more of their story as well, but as is almost always the case, history is usually recorded by the winners of world events, not its losers.

Regardless of whether or not I agree with Putin’s justification that entering Crimea was for the purpose of protecting his Naval fleet on the Black Sea and the large ethnic Russian population in this autonomous area of Ukraine, I am also quite certain that our leaders would have done the same thing for Americans had we been in similar shoes. At the same time, Putin’s justification for entering Crimea sets a dangerous precedent if gone unopposed as he could then feel free to enter any former territory, including Latvia, if he felt native Russians were in danger due to political instability.

Returning to the subject of Latvia, I will say that the people of Riga, Latvia’s capital city where we stayed, weren’t – to put it bluntly – all that friendly. You could say the same thing about New Yorkers though and at least in New York, the people don’t have the excuse that English isn’t their native language or that they had at one time been occupied by a foreign country whose leaders threw them in jail for saying the wrong things. Not say anything at all may have been something young Latvians quickly learned.

In spite of their lack of Midwestern, American smiles and nods of acknowledgement on city sidewalks, Latvian’s were an otherwise normal people, trying to make a living and enjoy the ups and downs of daily life. The people, particularly the women, were much taller than I had expected and they definitely had a liking for high fashion. The city itself was beautiful as well, a cobblestoned cross between Washington DC and Charleston, South Carolina.

A few days into our trip, a supermarket in Riga collapsed, killing 54 people and making international news. Several friends reached out to me through Facebook to make sure we were okay, recognizing the name of a city, Riga, which they normally would have glossed right over had I not been there. (Apparently, I’m not the only one whose sense of concern is heightened by familiarity.) In a strange turn of events, the popular Prime Minister of Latvia who had helped the country join the European Union and recover from the worldwide recession, suddenly resigned, taking the blame for the supermarket disaster. I say strange only because I couldn’t imagine, from an American point of view, Barrack Obama or any other President resigning over similar issues.

Given the disaster and the resulting resignation of the prime minister, there were several protests in the streets of Riga in front of the Mayor’s headquarters. The protests were smaller than those that had just started in Ukraine, but they were nevertheless very real. A coalition government would have to fill the vacuum for a time, which unsettled many, to say the least. Much to my wife’s chagrin, I walked among the protestors, each side hurling unknown verbal assaults at one another. Claiming to be a stupid American, I snapped a few shots with my camera and asked the police why they were protesting.

According to the police, some of the protesters were angry with the mayor’s office for the handling of the supermarket disaster. Later conversations with others suggested that some didn’t like the mayor of Riga, believing him to be a “puppet of Russia” and far too liberal in buying votes through costly social programs that benefited the few at the expense of many. While some in the United States have voiced similar opinions to the first point, the comment about the Mayor being a puppet of the Russians seemed strange to me, implying some type of corruption. Wasn’t this Latvia, after all?

While it may indeed be the country of Latvia, the large ethnic Russian populations here and in other former Russian territories like the Ukraine, maintain a powerful political influence just as some minority groups are collectively and independently very powerful in the United States’ democracy. Ethnic Russians may not, in fact, be corrupt in their ties to Russia, but like the entire State of Texas, just a lot more patriotic about their original Motherland.

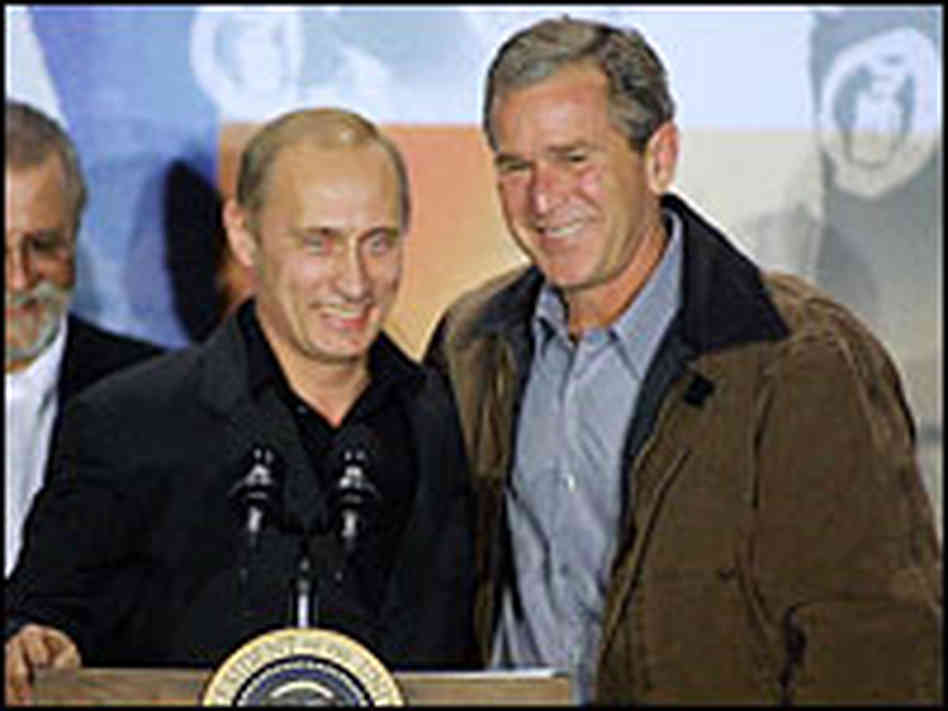

Heck, it could be that “Crimean Peninsula” in English means “Texas Panhandle.” No wonder George Bush and Vladimir Putin were so tight many years ago!

Kindest Regards,

Doug MacKay, CEO & CIO